India’s organic farming sector stands at a critical juncture, experiencing unprecedented growth in consumer demand while grappling with fundamental structural challenges that impede large-scale adoption. Despite ranking fourth globally in certified organic area and first in the number of organic producers, India captures only a fraction of the global organic trade value, highlighting the significant gap between potential and performance. The sector’s trajectory from 2020-2025 reveals a complex interplay of policy interventions, market dynamics, and farmer-level realities that collectively shape the future of sustainable agriculture in the country.[1][2]

📊 Explore the Interactive Dashboard

Dive deeper with dynamic tools and data you can explore yourself.

Current Market Trends and Growth Dynamics

Domestic Market Expansion

The Indian organic food market has demonstrated robust growth, expanding from approximately ₹1,800 crore in 2019 to ₹3,340 crore in 2023, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17%. Market projections indicate continued expansion, with estimates suggesting the sector could reach $21.99 billion by 2033, growing at a CAGR of 10.94%. This growth trajectory reflects increasing health consciousness among urban consumers, with 61% of metropolitan respondents aware of organic products, though only 12% regularly purchase them due to price sensitivity and trust concerns.[3][4][5]

The domestic organic market’s evolution from 2020-2025 has been characterized by several key trends. E-commerce platforms have revolutionized accessibility, with online marketplaces providing convenient access to organic products, particularly in urban areas. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this shift, as consumers became more health-conscious and sought chemical-free food products. However, significant challenges persist in rural and semi-urban markets, where awareness remains limited and affordability issues constrain adoption.[6][5][7]

Export Performance and Volatility

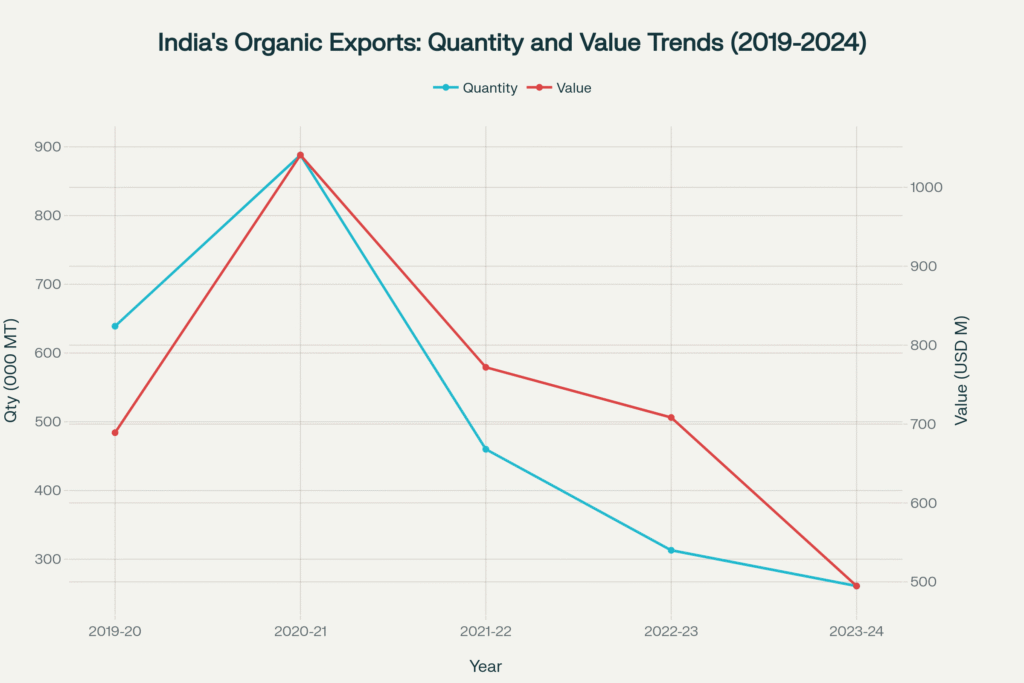

India’s organic export performance presents a paradoxical picture of both opportunity and challenge. Export data from 2019-2024 reveals significant volatility, with quantities peaking at 888,179 metric tonnes valued at $1,040.95 million in 2020-21, before declining to 261,029 metric tonnes worth $494.80 million in 2023-24. This dramatic decline underscores the fragility of India’s export competitiveness and highlights structural issues within the organic value chain.[8][9]

The Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) data shows that India exported organic products worth $708 million in 2022-23, a substantial decrease from previous years. Key export destinations include the United States, European Union, Canada, and Australia, with products dominated by oilseeds, pulses, cereals, tea, and spices. However, logistical challenges, certification delays, and quality control issues have led to consignment rejections, undermining India’s export credibility.[8][5]

Production Capacity and Potential

As of March 2024, India has 1,764,677.15 hectares under certified organic farming, with an additional 3,627,115.82 hectares under conversion. The country produced approximately 3.6 million metric tonnes of certified organic products in FY 2024, encompassing diverse categories including oilseeds, fiber, sugarcane, cereals, pulses, medicinal plants, tea, coffee, fruits, vegetables, and spices. Despite these impressive numbers, India’s share of global organic agricultural land remains modest, highlighting the untapped potential for expansion.[1][10][2]

Policy Landscape and Government Interventions

Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) Implementation

The Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana, launched in 2015 as a component of the National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture, represents the government’s flagship organic farming promotion initiative. The scheme provides comprehensive support to organic farmers through a cluster-based approach, offering ₹31,500 per hectare over three years, distributed across production support (₹15,000/ha), marketing and value addition (₹4,500/ha), certification (₹3,000/ha), and training (₹9,000/ha).[11]

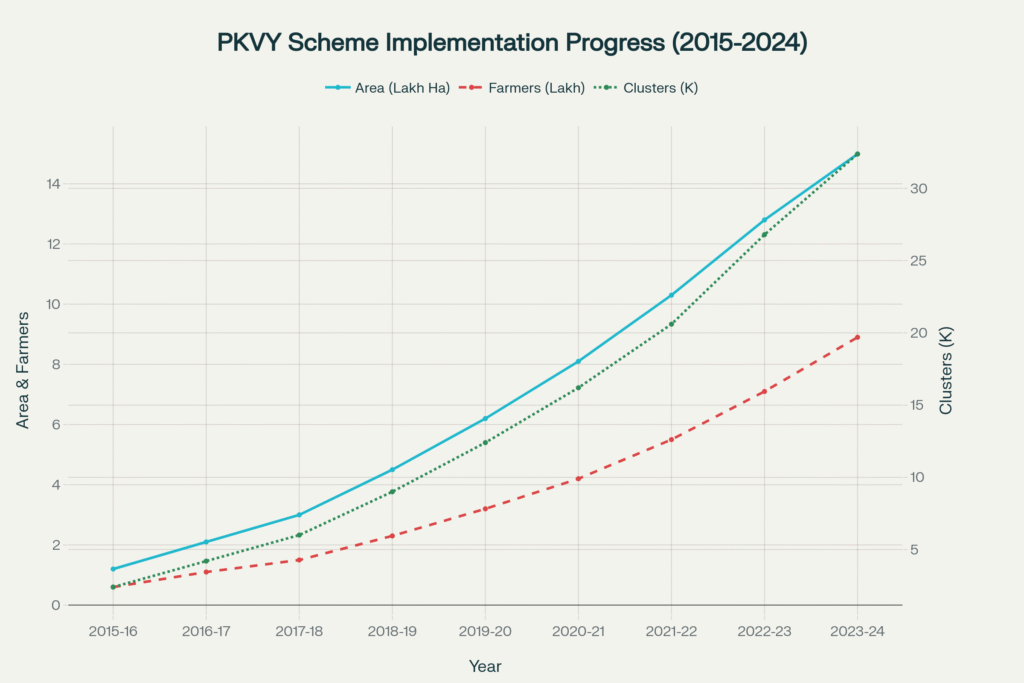

PKVY’s implementation has shown consistent progress, covering 14.99 lakh hectares through 52,289 clusters involving 25.30 lakh farmers as of December 2024. The scheme’s cluster approach facilitates Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) certification, enabling farmers to certify organic produce for domestic markets while building local capacity and community ownership. Financial assistance follows a 60:40 sharing pattern between central and state governments, with enhanced support (90:10) for northeastern and Himalayan states.[12][13][11]

National Programme for Organic Production (NPOP)

The National Programme for Organic Production serves as India’s primary framework for organic certification aligned with international standards. NPOP accreditation is mandatory for organic product exports, with over 10 lakh farmers registered under the program. The certification system involves rigorous third-party verification, ensuring compliance with international organic standards but also creating cost barriers for smallholder farmers.[8][14]

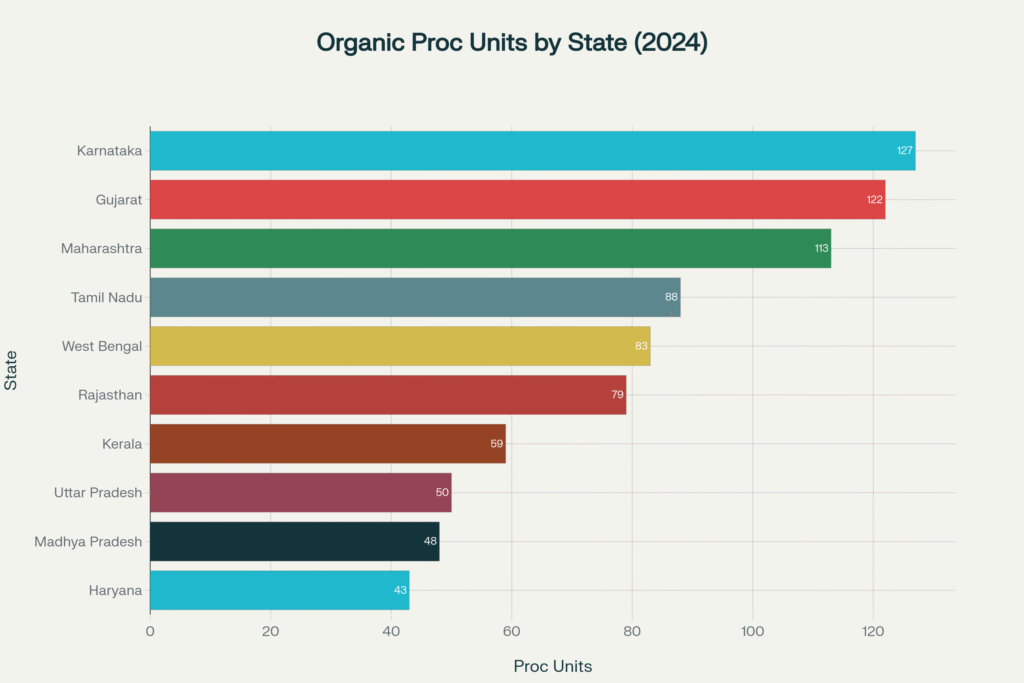

NPOP’s implementation has facilitated the establishment of 1,016 certified processing units across India, with Karnataka (127 units), Gujarat (122), and Maharashtra (113) leading in processing capacity. However, the system’s complexity and cost structure have generated criticism, particularly regarding accessibility for small and marginal farmers who constitute 85% of India’s farming community.[9][15]

NITI Aayog’s Strategic Vision

NITI Aayog has positioned organic and natural farming as crucial components of India’s sustainable development strategy. The organization’s 2023 report emphasizes leveraging agroecological approaches for clean and green villages, with plans to convert an additional 6.00 lakh hectares to organic farming under PKVY between 2022-23 and 2025-26. This ambitious target reflects the government’s commitment to scaling organic agriculture as part of broader environmental and rural development objectives.[16]

The Bhartiya Prakratik Krishi Paddhati (BPKP) sub-scheme, launched under PKVY in 2019-20, specifically promotes natural farming practices. Under BPKP, 4.09 lakh hectares have been brought under natural farming, representing an alternative approach that emphasizes indigenous knowledge and zero-input cultivation methods.[17][16]

Regional Success Stories and Case Studies

Sikkim: The Organic State Model

Sikkim’s transition to becoming the world’s first fully organic state provides valuable insights into successful large-scale organic conversion. The state’s journey began in 2003 with a legislative resolution to adopt organic farming, culminating in full organic status by 2016. The transformation involved a comprehensive policy framework including a gradual phase-out of chemical inputs, complete ban on synthetic pesticides and fertilizers by 2010, and substantial investment in farmer training and infrastructure development.[18][19][20]

The Sikkim Organic Mission, launched in 2010, provided crucial support for the transition, offering seeds, organic manure, and extensive training programs to over 66,000 farming families. The mission’s success can be attributed to strong political commitment, community participation, and integration of traditional knowledge with modern organic practices. Between 2015 and 2017, tourist arrivals increased by 50%, demonstrating the economic benefits of organic agriculture beyond direct farm income.[19][20][18]

However, Sikkim’s organic transition has not been without challenges. Studies indicate difficulties in pest management, with organic methods proving less effective against certain diseases and pests. Certification costs remain burdensome for small farmers, and market access continues to pose challenges despite organic status. The state’s experience highlights both the potential and limitations of comprehensive organic conversion.[21][22][23]

Kerala’s Spice Sector Initiatives

Kerala’s organic farming initiatives, particularly in spices and plantation crops, offer another model for sector-specific organic development. The state’s diverse agro-climatic conditions support cultivation of cardamom, black pepper, ginger, turmeric, and other high-value spices with strong export potential. The Wayanad Social Service Society (WSSS) has successfully organized over 10,000 farmers into approximately 400 local groups, covering more than 10,000 hectares under various stages of organic conversion.[24][25]

The spice sector’s organic transition has been driven by export market requirements, particularly from Middle Eastern countries where pesticide residue concerns have limited conventional spice imports. The Spices Board’s Quality Improvement Training Programme aims to address these challenges by promoting organic cultivation methods and reducing chemical residues in export products. Kerala Agricultural University’s three-year organic cardamom project has shown promising results, with organic cultivation demonstrating potential for premium pricing in international markets.[26][27]

Technological Innovation and Digital Solutions

Blockchain and Traceability Systems

The integration of blockchain technology and digital traceability systems represents a significant advancement in organic farming credibility and market access. Companies like Organic Ledger have developed blockchain-powered platforms that provide transparent, tamper-proof records of food production from farm to fork. These systems have already gained traction with major brands like Nestlé, Carrefour, and Starbucks, demonstrating their commercial viability.[7]

TraceX’s implementation in rural India illustrates the practical application of digital traceability systems. The platform enables field staff to collect farmer data, GPS coordinates, and production information through offline-capable mobile applications, creating comprehensive digital records that support certification and audit processes. QR codes linked to blockchain databases allow consumers to verify product authenticity and trace the complete supply chain journey.[28][29][30]

Digital traceability addresses critical challenges in organic certification and consumer trust. According to research, blockchain-traced products face 30% fewer rejection rates in export markets where traceability is often a regulatory requirement. The technology ensures that no data along the supply chain can be altered or hidden, significantly reducing fraud and counterfeit organic products.[28][7]

Precision Agriculture and IoT Integration

The adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, satellite monitoring, and artificial intelligence in organic farming has enhanced productivity while maintaining certification compliance. These technologies enable real-time monitoring of soil health, irrigation needs, and pest pressure, allowing farmers to make data-driven decisions that optimize yield while adhering to organic standards.[28][7]

Kisan Ledger, a complementary platform to Organic Ledger, empowers farmers to increase production by 25% while reducing agricultural inputs by 30%. The system connects farmers directly with buyers, ensuring traceable, authentic products that meet consumer and regulatory demands. Such technological integration represents a paradigm shift from traditional record-keeping methods to sophisticated digital management systems.[7]

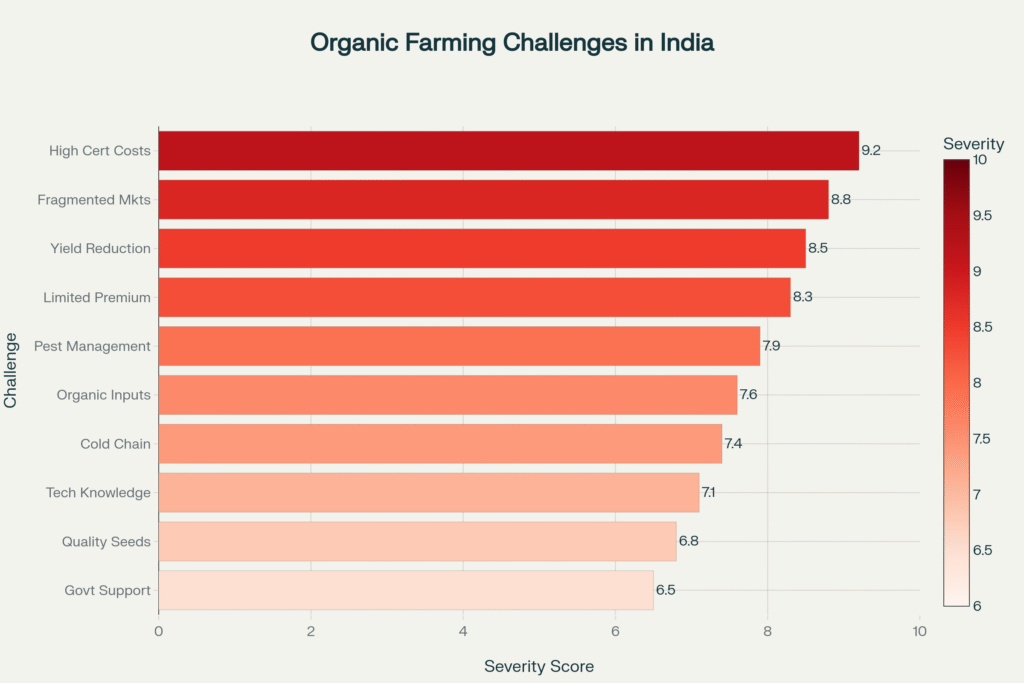

Challenges and Constraints

Certification Costs and Accessibility

High certification costs emerge as the most significant barrier to organic farming adoption in India. NPOP certification can cost between ₹50,000 to ₹2 lakhs annually, depending on operation size and certifying agency. For a typical small farmer, these costs represent a substantial investment that often cannot be justified without guaranteed premium pricing. The three-year conversion period, during which farmers incur organic production costs without receiving premium prices, further exacerbates financial constraints.[14][5][31][32]

The Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) was designed to address cost barriers through community-based certification, but its limitation to domestic markets restricts export opportunities. Many farmers remain confused about certification requirements, with over 30% of certified organic farmers not fully understanding which certification system they belong to or the markets they serve.[5][33]

Market Fragmentation and Supply Chain Issues

Fragmented markets and inadequate supply chain infrastructure constitute the second most severe challenge facing organic farmers. Over 70% of certified organic produce in India is sold as conventional due to poor labelling, lack of certification trust, and inadequate rural collection centers. The absence of dedicated organic supply chains means that products often get mixed with conventional produce during transportation and storage, nullifying certification benefits.[5][31]

Cold storage and transportation infrastructure remain critically inadequate, particularly for perishable organic produce. The requirement for separate storage and handling to avoid cross-contamination with conventional products is often not met by existing supply chain infrastructure. Direct linkages between producers and processors or retailers are limited, forcing farmers to depend on middlemen who may not recognize organic premiums.[31][34]

Technical Knowledge and Input Availability

Limited technical knowledge and inadequate availability of organic inputs present significant operational challenges. Many farmers lack sufficient training in organic cultivation techniques, particularly regarding pest management and soil fertility maintenance. The transition period typically involves a 20-30% yield reduction as soil biology recovers from chemical input dependency, requiring farmers to accept short-term income losses.[5][34][35]

Organic inputs such as biofertilizers, biopesticides, and organic seeds remain expensive and difficult to access in many regions. The quality and effectiveness of available organic inputs are often inconsistent, leading to variable crop performance and farmer dissatisfaction. Extension services specifically focused on organic farming techniques are limited, leaving farmers to rely on trial-and-error methods.[31][34]

Climate Resilience and Environmental Benefits

Soil Health and Carbon Sequestration

Organic farming practices contribute significantly to climate change mitigation and adaptation through enhanced soil health and carbon sequestration. Research indicates that organic soils contain 13% higher soil organic matter and 44% higher long-term carbon storage compared to conventionally managed soils. These benefits result from practices such as crop rotation, cover cropping, composting, and the elimination of synthetic fertilizers that release nitrous oxide.[36]

The improved soil structure in organic systems enhances water retention capacity, making farms more resilient to drought and flooding. High soil organic matter content helps prevent nutrient and water loss, creating more stable production systems under variable climate conditions. Organic agriculture’s emphasis on biodiversity conservation also supports ecosystem services that contribute to climate resilience.[35][37][38][36]

Adaptation Strategies and Diversification

Organic farming encourages crop diversification, which enhances resilience to climate change by reducing risk through variety. Growing multiple crops reduces the likelihood of total crop failure due to adverse weather conditions or pest outbreaks. Agroforestry practices, commonly integrated with organic systems, provide additional benefits including shade, windbreaks, and improved soil structure.[35][37]

Cover cropping and green manuring, fundamental practices in organic systems, improve soil health, reduce erosion, and enhance water retention. These practices make organic farms more adaptable to climate variability and extreme weather events. The elimination of synthetic pesticides also reduces environmental pollution and supports beneficial insect populations that contribute to ecosystem stability.[37][36][38][35]

Future Opportunities and Recommendations

Export Market Development

India’s potential to emerge as a global organic hub remains substantial, contingent on addressing current structural challenges. The global organic market, valued at approximately $138 billion, presents significant opportunities for Indian exporters who currently capture less than 1% of the market. Key strategies for export development include improving post-harvest handling, strengthening certification systems, and building dedicated organic supply chains.[8][5]

Strategic focus on high-value products such as medicinal plants, processed foods, and value-added spice products could significantly enhance export revenues. The development of organic export zones, similar to Special Economic Zones, could provide necessary infrastructure and support services for export-oriented organic production. Partnerships with international organic retailers and participation in global organic trade fairs could improve market access and brand recognition.[5][8]

Digital Integration and Innovation

The integration of digital technologies presents transformative opportunities for organic farming in India. Blockchain-based traceability systems can address trust deficits and meet increasing consumer demand for transparency. Mobile applications for farmer advisory services, certification management, and market linkage can reduce transaction costs and improve efficiency.[28][30][7]

Precision agriculture technologies, when adapted for organic systems, can optimize resource use while maintaining certification compliance. Satellite-based monitoring systems can provide real-time crop health assessment, enabling timely interventions and yield optimization. Digital platforms connecting organic producers directly with consumers can eliminate intermediaries and improve price realization.[39][7][28]

Policy Recommendations

A comprehensive policy framework addressing current constraints while leveraging emerging opportunities is essential for sector growth. Key recommendations include establishing a farmer-friendly, cost-effective certification policy that reduces barriers for small farmers while maintaining quality standards. The development of organic input manufacturing facilities through public-private partnerships could address supply constraints and reduce costs.[15][5][31][34]

Investment in organic-specific infrastructure including cold storage, processing facilities, and transportation networks is crucial for value chain development. The creation of organic commodity exchanges could provide price discovery mechanisms and market stability for organic producers. Integration of organic farming in agricultural education curricula and enhanced extension services would build necessary technical capacity.[5][31][34][40]

Conclusion and Strategic Outlook

The future of organic farming in India during 2020-2025 represents both unprecedented opportunity and significant challenge. While the sector has demonstrated remarkable growth in area coverage, farmer participation, and policy support through initiatives like PKVY, fundamental constraints in certification costs, market access, and supply chain infrastructure continue to limit its potential. Success stories from Sikkim and Kerala provide valuable lessons but also highlight the complexity of large-scale organic conversion.

The integration of digital technologies, particularly blockchain-based traceability systems and precision agriculture tools, offers pathways to address traditional constraints while improving competitiveness in global markets. Climate change concerns and increasing consumer health consciousness create favorable conditions for organic agriculture expansion, but realizing this potential requires coordinated policy interventions, infrastructure development, and capacity building initiatives.

India’s position as a global organic leader will ultimately depend on its ability to balance the needs of small farmers with the demands of modern organic markets, leveraging traditional knowledge while embracing technological innovation. The sector’s trajectory toward 2025 and beyond will be determined by the effectiveness of current policy interventions in addressing structural challenges while building sustainable, scalable organic agriculture systems that contribute to both farmer prosperity and environmental sustainability.

🌱 FAQs on Organic Farming in India (2020–2025)

What is the current size of the organic food market in India and how fast is it growing?

The Indian organic food market expanded from ₹1,800 crore in 2019 to ₹3,340 crore in 2023, with a CAGR of 17%. It is projected to reach $21.99 billion by 2033, growing at 10.94% annually

How does India rank globally in organic farming?

India ranks 4th in certified organic area and 1st in the number of organic producers. However, it captures only a small share of the global organic trade value, highlighting untapped potential

What are India’s top export destinations for organic products?

Key export markets include the United States, European Union, Canada, and Australia, with major products being oilseeds, pulses, cereals, tea, and spices

Why has India’s organic export performance been volatile?

Exports peaked in 2020–21 at 888,179 metric tonnes worth $1.04 billion, but declined to 261,029 MT worth $494.80 million in 2023–24 due to certification delays, quality control issues, and logistical challenges

How much land is under organic farming in India?

As of March 2024, India has 1.76 million hectares certified organic and another 3.62 million hectares under conversion, producing about 3.6 million MT of organic products annually

What are the major government schemes supporting organic farming?

- Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY): cluster-based approach with financial support of ₹31,500 per hectare over 3 years.

- National Programme for Organic Production (NPOP): provides internationally aligned certification, required for exports.

- Bhartiya Prakratik Krishi Paddhati (BPKP): promotes natural farming practices

Which states are leading in organic farming initiatives?

- Sikkim: world’s first fully organic state.

- Kerala: strong in organic spices (pepper, cardamom, turmeric).

- Karnataka, Gujarat, and Maharashtra: top in organic processing units

What are the biggest challenges faced by organic farmers in India?

- High certification costs (₹50,000–₹2 lakh annually).

- Yield losses during transition (20–30%).

- Limited market access and fragmented supply chains (70% of certified organic sold as conventional).

- Poor infrastructure for cold storage and transportation

How is technology helping the organic farming sector?

- Blockchain & Traceability: builds consumer trust, reduces fraud, and lowers export rejection rates.

- IoT & AI: improve soil, pest, and irrigation management.

- Digital platforms: connect farmers directly with buyers, cutting out middlemen

What are the future opportunities for India’s organic farming sector?

- Expanding exports to capture a larger share of the $138 billion global organic market.

- Value addition in spices, medicinal plants, and processed foods.

- Developing organic export zones and dedicated supply chains.

- Strengthening farmer-friendly certification and digital integration

- https://www.nextias.com/

- https://orgprints.org/

- https://www.businesswire.com/

- https://m.thewire.in/

- https://earth5r.org/

- https://www.techsciresearch.com/

- https://biofach-india.com/

- https://apeda.gov.in/

- https://www.pib.gov.in/

- https://apeda.gov.in/

- https://www.pib.gov.in/

- https://dmsouthwest.delhi.gov.in/

- https://darpg.gov.in/

- https://orgprints.org/

- https://jmra.in/

- https://www.niti.gov.in/

- https://www.inseeworld.com/

- https://byjus.com/

- https://www.studyiq.com/

- https://www.forbes.com/

- https://bpasjournals.com/

- https://www.caluniv.ac.in/

- https://www.indiaspend.com/

- https://keralaagriculture.gov.in/

- https://cds.edu/

- https://e-startupindia.com/

- https://theorganicmagazine.com/

- https://earth5r.org/

- https://tracextech.com

- https://tracextech.com/

- https://www.researchpublish.com/

- https://agriculture.institute

- https://farmonaut.com/

- https://justagriculture.in/

- https://humicfactory.com/

- https://www.organic-center.org/

- https://www.ils.res.in/

- https://bharatvarshnaturefarms.com/

- https://farmonaut.com/

- https://www.niti.gov.in/

- https://apeda.gov.in

- https://apeda.gov.in/

- https://byjus.com

- https://diragri.assam.gov.in

- https://www.fibl.org/

- https://apeda.gov.in/

- https://www.myscheme.gov.in

- https://apeda.gov.in/

- https://www.china-briefing.com/

- https://indianexpress.com/

- https://www.volza.com/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/

- https://www.india-briefing.com/

- https://www.ambujafoundation.org/

- https://www.icrier.org/pdf/wp168.pdf

- https://reasonstobecheerful.world/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://keralabiodiversity.org/

- https://idronline.org/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://agrocops.org/

- https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/

- https://visionias.in/

- https://organicoperators.au/

- https://www.jetir.org/

- https://www.niti.gov.in/

- https://openknowledge.fao.org/

- https://www.drishtiias.com/

- https://www.fao.org/

- https://niti.gov.in/

- https://www.ceew.in/

- http://www.fao.org/

- https://www.niti.gov.in/

- https://openknowledge.fao.org/

- https://www.pib.gov.in/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

Get Involved!

Leave a Comment