The agricultural crisis plaguing India has reached unprecedented dimensions, with farmer suicides emerging as one of the most pressing socio-economic challenges of our time. Between 1995 and 2022, approximately 397,540 farmers and agricultural laborers have died by suicide—a staggering figure that represents not just numbers, but shattered families, abandoned fields, and communities in despair. This crisis, concentrated primarily in states like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh, reflects deeper systemic failures in India’s agricultural framework, demanding urgent, evidence-based interventions that address both immediate distress and long-term sustainability.[1][2]

📊 Explore the Interactive Dashboard

Dive deeper with dynamic tools and data you can explore yourself.

Understanding the Magnitude and Trends

Historical Pattern and Recent Developments

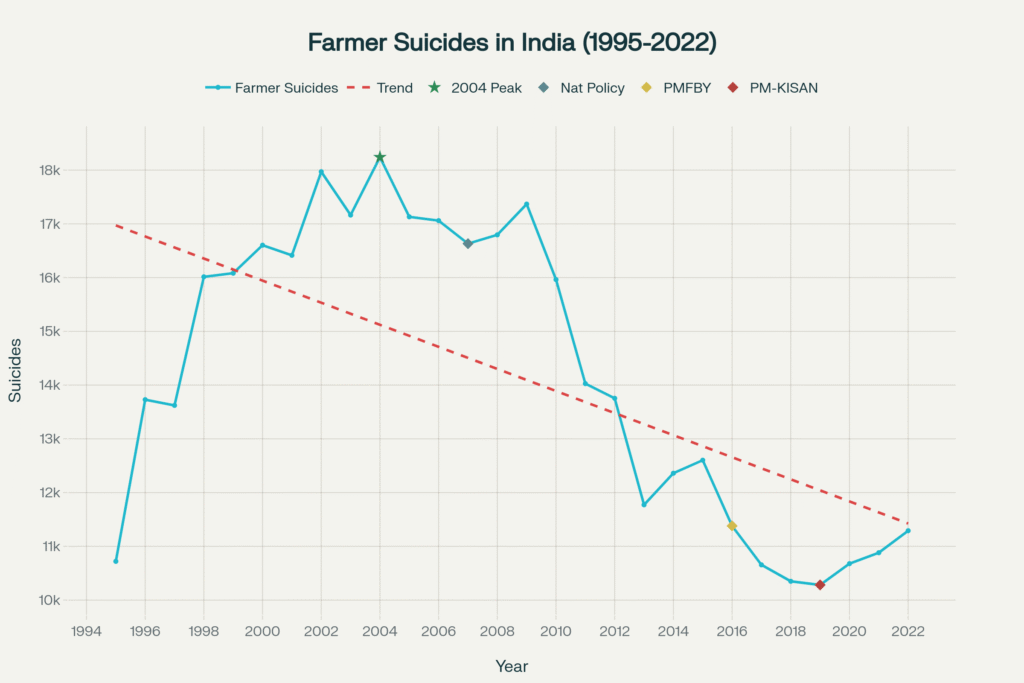

The trajectory of farmer suicides in India reveals a complex pattern of peaks and gradual decline following policy interventions. The crisis reached its zenith in 2004 with 18,241 recorded suicides, marking the darkest period in India’s agricultural history. However, recent data indicates a notable 38.1% reduction from peak levels, with 11,290 suicides reported in 2022, translating to approximately 31 farmer deaths by suicide daily.[1][2][3][4]

This decline, while encouraging, must be contextualized within broader demographic and economic changes in rural India. The average annual suicide count of 14,198 over the 28-year period demonstrates the persistent nature of agrarian distress, with periodic fluctuations corresponding to monsoon patterns, policy changes, and economic cycles.[3][1]

Geographic Concentration and State-wise Analysis

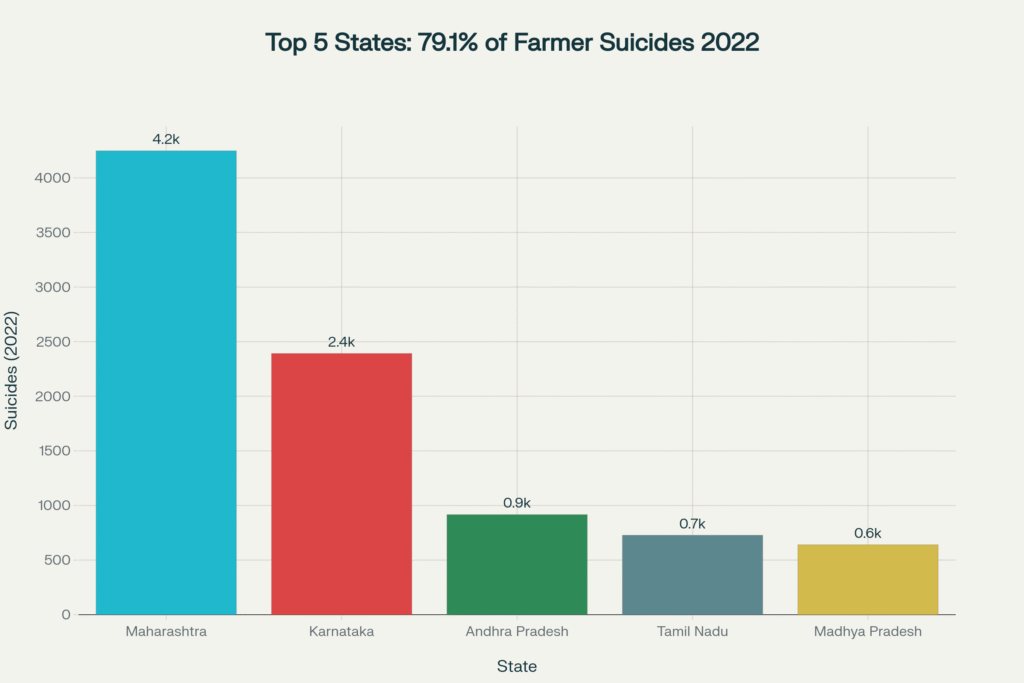

The geographic distribution of farmer suicides reveals stark regional disparities, with five states accounting for 79.1% of all cases in 2022. Maharashtra continues to lead tragically with 4,248 suicides (37.6% of the national total), followed by Karnataka (2,392), Andhra Pradesh (917), Tamil Nadu (728), and Madhya Pradesh (641).[3][5]

The concentration in these states reflects specific vulnerabilities: Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region alone witnessed over 60,000 farmer deaths between 1995 and 2013. This geographic clustering indicates that certain agro-ecological zones, characterized by cotton cultivation, rain-fed agriculture, and limited irrigation infrastructure, create particularly high-risk environments for farmer distress.[1][6][7]

Root Causes: A Multi-Dimensional Crisis

Economic Determinants: The Debt Trap

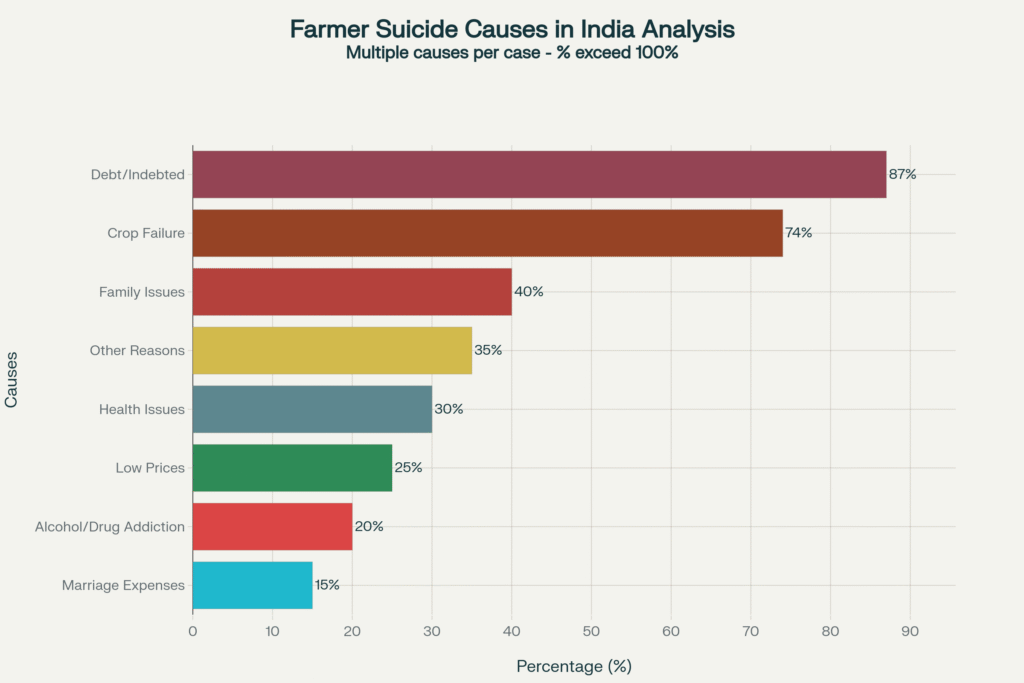

Research consistently identifies indebtedness as the primary driver, affecting 87% of suicide cases. The debt crisis stems from multiple interconnected factors: rising input costs, declining productivity, and inadequate price realization. Particularly concerning is the shift from institutional to non-institutional credit sources, with private moneylenders charging interest rates between 24-36% annually compared to 9-12% from formal banking institutions.[2][8][9][10][6][11]

The Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme, despite its intended benefits, has paradoxically contributed to serial indebtedness. Farmers increasingly divert agricultural loans for non-farm expenses including healthcare, education, and social obligations, creating a “development debt trap” where survival needs override productive investments. By 2024, KCC disbursements exceeded $120 billion, yet the underlying debt crisis persists.[12]

Agricultural Challenges: Climate and Crop Vulnerabilities

Climate variability emerged as a significant suicide risk factor, with research demonstrating that temperatures above 20°C during growing season correlate with increased suicide rates—approximately 70 additional deaths per 1°C temperature increase. The study spanning 47 years found that 59,300 suicides between 1980-2013 can be attributed to climate change impacts, representing 6.8% of the upward trend in farmer suicides.[13]

Cash crop cultivation, particularly cotton, represents a high-risk agricultural pattern. Studies identify three specific risk characteristics: farmers growing cash crops like coffee and cotton, those with marginal farms under one hectare, and those carrying debts above ₹300. These characteristics combine to create vulnerability patterns that explain nearly 75% of state-level suicide variations.[1][14]

Social and Psychological Factors

The crisis extends beyond economic parameters to encompass social isolation, family discord, and mental health challenges. Research in Vidarbha revealed that debt-related stress significantly outranked crop failure as a suicide trigger, with family problems, alcohol addiction, and social obligations creating compound vulnerabilities.[9][6][15]

Mental health infrastructure remains critically inadequate, with only one psychiatrist per 250,000 people and less than one mental health worker per 100,000 population. This shortage leaves farmers with limited access to psychological support during crisis periods.[16][17]

Policy Interventions and Their Effectiveness

Government Schemes: Mixed Results

The Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), launched in 2016, represents the most significant crop insurance intervention, covering over 5.5 crore farmers with ₹1.8 lakh crore sum insured. Spatiotemporal analysis in Maharashtra demonstrates notable reductions in suicide clusters following PMFBY implementation, particularly in high-risk districts like Aurangabad, Nagpur, and Amravati.[18][19]

However, implementation challenges persist: only 15 states have established mandated grievance redressal committees, and two-thirds of farmers remain unaware of the scheme. Several states including Gujarat, Jharkhand, and West Bengal have opted out citing high premium costs.[19]

The PM-KISAN scheme, providing ₹6,000 annual direct income support, has reached over 10 crore beneficiaries. Studies in Uttar Pradesh demonstrate improved farm incomes among beneficiaries, though impact on suicide prevention remains difficult to quantify due to multiple confounding variables.[20][21]

Loan Waiver Policies: Temporary Relief or Long-term Solution?

Loan waiver schemes have provided temporary relief but failed to address structural issues. The 2008 Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme benefited 36 million farmers at a cost of ₹65,000 crore. However, subsequent increases in farmer suicides suggest that debt waivers, while providing immediate relief, may create moral hazard and fail to address underlying productivity and market access issues.[22][23][24][25]

Economic analysis indicates that loan waivers may cost up to 2.6% of GDP while potentially straining public sector banks already facing asset quality challenges. Alternative approaches focusing on debt restructuring, interest subvention, and productivity enhancement may prove more sustainable.[23][24]

Successful Interventions and Best Practices

Community-Based Mental Health Models

The VISHRAM program in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region demonstrates effective community-based intervention. This initiative provides psychological support through trained community health workers, offering a scalable model for rural mental health delivery. The program recognizes that at least 50% of farmer suicides globally involve depressive disorders or alcohol use disorders.[26]

Kerala’s psychological autopsy studies reveal protective factors including family support, community engagement, and access to mental health services. Research identifies three protective factor categories: personal (autonomy, problem-solving skills, resilience), social (family, peer support, community belonging), and environmental (government support, rural lifestyle, recognition).[16][17]

Self-Help Group Interventions

Self-Help Groups (SHGs) have emerged as effective financial inclusion and social support mechanisms. NABARD’s SHG-Bank Linkage Programme covers nearly 100 million households, with over 84% being women-exclusive groups. PRADAN’s interventions have reached 651,748 smallholder farmers, demonstrating significant impacts on food security and income stability.[27][28][29][30]

The microfinance model addresses both financial access and social capital formation. Studies in Jharkhand demonstrate that SHG members experience improved livelihood outcomes across multiple dimensions including human, social, natural, physical, and financial capital.[29][31]

Technology-Driven Solutions

Artificial Intelligence and digital agriculture initiatives show promising results in addressing farmer distress. The AI4AI (AI for Agriculture Innovation) program in Telangana demonstrated remarkable outcomes: 7,000 participating farmers reported doubled incomes ($800 per acre per cycle), 21% yield increases, and reduced input costs.[32][33]

Blockchain technology applications in agriculture address transparency and trust issues in supply chains. Projects like KRanTi offer blockchain-based credit systems that could reduce farmer dependence on informal lending sources. Jharkhand’s blockchain-based seed distribution system eliminates intermediaries and prevents fraud while ensuring direct farmer access.[34][35][36][37]

Climate Change and Agricultural Resilience

Drought-Suicide Nexus

Rainfall deficits significantly correlate with increased farmer suicide rates. Research across five high-suicide states (Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana) reveals that 25% rainfall deficit can increase annual farmer suicides from 810 to 1,188 cases.[38][13]

Over three-quarters of Chhattisgarh and nearly two-thirds of Maharashtra now classify as highly drought-prone. This expanding vulnerability necessitates climate-resilient agricultural practices and enhanced social protection systems for weather-related income shocks.[38]

Adaptation Strategies

Diversification into allied activities including dairy, animal husbandry, poultry, beekeeping, horticulture, and fisheries offers income stability during crop failures. Government initiatives promoting value addition through food processing and investments in cold storage infrastructure can reduce post-harvest losses that currently account for up to 40% of agricultural output.[39][23][25]

International Comparisons and Lessons

Global Farmer Suicide Patterns

Farmer suicide represents a global phenomenon with concerning patterns worldwide. Australia records one farmer suicide every 10 days, the UK experiences one weekly, and France witnesses one every two days. In contrast, India’s rate of one farmer suicide every 52 minutes highlights the exceptional severity of the crisis[calculated from current data].[40][41][42]

United States farmers face suicide rates 3.5 times higher than the general population, with similar risk factors including financial stress, social isolation, and access to lethal means. Australian research identifies two distinct suicide pathways: acute situational (financial/interpersonal stress) and protracted (linked to mental illness).[41][43][40]

Policy Learnings

International experiences emphasize the importance of integrated approaches. Australia’s drought response includes rapid mobilization of mental health professionals alongside financial support. The US crop insurance program represents the only major federally managed insurance system outside Medicare, demonstrating political commitment to agricultural risk mitigation.[42]

Emerging Solutions and Innovative Interventions

Digital Mental Health Platforms

India’s expanding mental health helpline infrastructure includes Kiran (1800-599-0019), Tele MANAS (14416), and specialized services like the Vandrevala Foundation (24/7 multilingual support). Mobile technology adoption enables real-time crisis intervention and ongoing psychological support.[44][45]

AI-based depression detection systems show promising results with 96.59% accuracy in identifying at-risk farmers. Integration of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) assessments with machine learning models enables large-scale mental health screening in agricultural populations.[46]

Financial Innovation

Blockchain-based lending platforms offer transparent, efficient alternatives to traditional credit systems. Smart contracts can automate loan disbursement and repayment, reducing transaction costs and eliminating intermediary exploitation. Decentralized finance (DeFi) applications could democratize agricultural credit access while maintaining accountability.[34][35][36]

Parametric insurance products linked to weather data and satellite imagery enable faster claim processing and reduced assessment costs. Machine learning algorithms can predict crop losses and trigger automatic payouts, eliminating bureaucratic delays that often exacerbate farmer distress.[18][33]

Policy Recommendations and Sustainable Interventions

Immediate Measures

Comprehensive debt relief must move beyond periodic loan waivers toward structured debt restructuring with productivity linkages. Interest rate caps for agricultural credit combined with enhanced institutional credit access can reduce dependence on exploitative informal lending.[11][24]

Crisis intervention systems require integration of mental health professionals into agricultural extension services. District-level counseling centers staffed by trained psychologists and mobile crisis response teams for remote areas can provide timely support during peak stress periods.[16][17]

Medium-term Reforms

Diversification support through integrated farming systems should emphasize allied activities that provide stable income streams. Value chain development initiatives connecting farmers directly to processing units and retail markets can improve price realization and reduce middleman exploitation.[39][27][47][25]

Climate adaptation programs must prioritize drought-resistant crop varieties, efficient irrigation systems, and weather-indexed insurance products. Soil health improvement initiatives and precision agriculture technologies can enhance productivity while reducing input dependencies.[38][13][32][33]

Long-term Structural Changes

Agricultural market reforms should focus on creating transparent, competitive markets with direct farmer-consumer linkages. Digital platforms enabling price discovery, quality certification, and supply chain integration can empower farmers with better market access.[32][35]

Education and skill development programs targeting rural youth can reduce pressure on agricultural land while creating alternative employment opportunities. Agri-preneurship initiatives and technology adoption support can transform farming from subsistence to enterprise-oriented activity.[27][48]

Mental Health Infrastructure

Comprehensive mental health integration requires training agricultural extension workers in basic psychological first aid and crisis identification protocols. Community-based mental health programs leveraging existing social networks and traditional support systems can provide culturally appropriate interventions.[26][17]

Substance abuse prevention and treatment programs addressing alcohol and drug addiction—identified in 20% of suicide cases—need integration with broader mental health services. Family counseling and social support systems can address interpersonal stressors that compound economic vulnerabilities.[15][16]

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

Data Systems Enhancement

Real-time monitoring systems utilizing satellite imagery, weather data, and crop conditions can enable predictive analytics for identifying high-risk regions and periods. Integration of NCRB suicide data with agricultural statistics can improve understanding of causation patterns and intervention effectiveness.[3][4][18][13]

Digital platforms for farmer registration and service delivery can enable targeted interventions based on risk profiling. Blockchain-based identity and credit history management can improve access to formal financial services while preventing over-indebtedness.[32][34][36][37]

Impact Assessment Methodologies

Longitudinal studies tracking farmer well-being indicators beyond suicide rates—including mental health scores, debt-to-income ratios, productivity measures, and social capital indices—can provide comprehensive intervention assessment. Randomized controlled trials of different intervention models can generate evidence for scaling successful approaches.[18][26][29][17]

Conclusion: Pathways Forward

The farmer suicide crisis in India represents a complex intersection of economic vulnerability, social isolation, climate stress, and systemic policy failures. While the 38.1% reduction in suicide rates from peak levels demonstrates that targeted interventions can achieve meaningful impact, the persistence of over 11,000 annual deaths underscores the urgent need for comprehensive, sustained action.[3][4]

Successful interventions must address multiple dimensions simultaneously: providing immediate financial relief through debt restructuring and income support, building long-term agricultural resilience through diversification and technology adoption, and establishing robust mental health support systems integrated with rural development programs.[18][26][17]

The emergence of digital technologies, blockchain platforms, and AI-driven agricultural services offers unprecedented opportunities to transform farming from a high-risk, low-return activity to a sustainable, profitable enterprise. However, technology adoption must be coupled with human-centered approaches that recognize farmers as stakeholders rather than beneficiaries, engaging them as partners in solution design and implementation.[26][27][32][34][33]

International experiences demonstrate that farmer suicide is preventable through coordinated policy action. India’s scale and diversity present unique challenges, but also unique opportunities to develop replicable models that can inform global agricultural development strategies.[40][41][42][32][35]

The path forward requires political commitment, institutional coordination, and sustained investment in both technological innovation and human development. Breaking the cycle of farmer suicides demands nothing less than a fundamental transformation of India’s agricultural ecosystem—from production systems and market structures to social support networks and mental health services. The lives and livelihoods of millions of farming families depend on the urgency and effectiveness of this transformation.

Only through such comprehensive, evidence-based interventions can India achieve the vision of prosperous, sustainable agriculture that honors the fundamental role farmers play in national food security and economic development. The data is clear, the solutions are emerging—what remains is the collective will to act with the urgency this crisis demands.

FAQs on Farmer Suicides in India

Why do so many farmers in India die by suicide?

Farmer suicides are driven by a mix of debt, rising input costs, crop failures, climate shocks, poor market access, and lack of mental health support. Indebtedness is the most common factor, affecting about 87% of cases

Which states are most affected by farmer suicides?

Maharashtra leads with nearly 38% of the national total, followed by Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Madhya Pradesh. These states account for nearly 80% of all cases

Has the situation improved in recent years?

Yes. Suicides peaked in 2004 (18,241 cases) but declined by about 38% by 2022 (11,290 cases). However, over 30 farmers still die by suicide every day, so the crisis is far from over

How does climate change affect farmer suicides?

Higher temperatures and rainfall deficits increase suicide risks. A 1°C rise during growing season has been linked to 70 additional suicides per year

Are government loan waivers an effective solution?

Loan waivers provide short-term relief but do not fix structural issues like low productivity, dependence on informal lenders, or poor market access. They may also strain the economy

Which government schemes have shown positive results?

The PM Fasal Bima Yojana (crop insurance) reduced suicide clusters in some districts, and PM-KISAN income support improved farm incomes. But awareness, coverage, and implementation remain limited

What role does mental health play in farmer suicides?

Mental health is a critical factor. Many farmers suffer from untreated depression, alcohol addiction, or social stress. India has just 1 psychiatrist per 250,000 people in rural areas, leaving huge gaps in support

Have any community-based interventions worked?

Yes. Programs like VISHRAM in Vidarbha and Self-Help Groups (SHGs) have shown success in reducing distress by offering counseling, peer support, and alternative income opportunities

How do Indian farmer suicides compare globally?

Globally, farmer suicides are a problem in countries like Australia, the US, and France. But India’s rate—one farmer suicide every 52 minutes—remains among the world’s most severe

What are the most important solutions going forward?

Solutions include debt restructuring (not just waivers), better credit access, climate-resilient farming, allied income activities (dairy, poultry, fisheries), improved market linkages, and robust rural mental health programs

Work Cited

- https://en.wikipedia.org/

- https://byjus.com/

- https://www.statista.com/

- https://www.indiatracker.in/

- https://arfjournals.com/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://papers.ssrn.com/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/

- https://www.pnas.org/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://jivresearch.org/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://www.nature.com/

- https://www.pmfias.com/

- https://desagri.gov.in/

- https://www.pib.gov.in/

- https://ddnews.gov.in/

- https://www.frbsf.org/

- https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/

- https://www.ijcmas.com/

- https://www.indiawaterportal.org/

- https://ngobox.org/

- https://www.saveindianfarmers.org/

- https://www.findevgateway.org/

- https://www.nabard.org/

- https://ncwapps.nic.in/

- https://www.weforum.org/

- https://indiaai.gov.in/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

- https://www.journalpressindia.com/

- https://www.ijraset.com/

- https://coingeek.com/

- https://www.iied.org/

- http://www.iaset.us/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://stacks.cdc.gov/

- https://www.talktoangel.com/

- https://progress.guide/

- https://etasr.com/

- https://www.ambujafoundation.org/

- https://www.mmpc.in/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://www.edengreen.com/

- https://depwd.gov.in/

- https://sageuniversity.edu.in/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/

- https://allduniv.ac.in/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/

- https://justagriculture.in/

- https://ras.org.in/

- https://sabrangindia.in/

- https://mu.ac.in/wp-content/

- https://journals.scholarpublishing.org/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://www.jetir.org/

- https://csrbox.org/

- https://sansad.in/

- https://www.3ieimpact.org/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/

- https://www.mshrc.gov.in/

- https://pmfby.gov.in

- https://vattikutifoundation.com/

- https://schemes.vikaspedia.in/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- http://soppecom.org/

- https://www.france24.com/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://fid4sa-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/

- https://www.andhrauniversity.edu.in/

- https://www.reuters.com/

- https://bpasjournals.com/

- https://www.farmersprideinternational.org

- https://bankofmaharashtra.in/

- https://www.sakalrelieffund.com/

- https://csrbox.org/

- https://icallhelpline.org

- https://desagri.gov.in/

- https://give.do/

- https://www.istm.gov.in/

- https://scholar.harvard.edu/

- https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://www.joghr.org/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://www.rrh.org.au

- https://www.isec.ac.in/

- https://ncgg.org.in/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/

- https://uknowledge.uky.edu/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/

- https://www.mguindia.com/

- https://geneticliteracyproject.org/

- https://www.antino.com

- https://www.nabard.org/

- https://www.thelivelovelaughfoundation.org/

Get Involved!

Leave a Comment